Capital Structures + OpCo/PropCo

blueprints for industry innovation

Good morning,

Today’s newsletter:

An amalgamation of thoughts on how atoms-based opportunities are getting financed at a high level.

Bits-based businesses are what we all know and love: software and data. High margins, relatively uncomplicated playbooks post-initial R&D, and large markets all yield a profile that has come to attract a wide range of investors. Appetite for risk still dictates the earliest stages and the eventual payoff, but at the other end of the spectrum in the publics: technology companies are attractive to shareholders that prioritize cash flow, dividends, and maturity.

Whatever your risk profile, you can find a bits-based business.

Atoms? That’s where it gets complicated.

Perhaps though, it’s better to distinguish between asset-light and asset-based businesses. Investors still love asset-light strategies. And they’ve parlayed Uber, Airbnb, and plenty more into massive equity growth. These companies are all coordinating atoms but leaving the atoms in someone else’s hands.

All else equal, asset-light is preferred. There’s less inherent complications, you take on no operating risk, and you can make the world more efficient without as much asset risk.

There’s always an inherent unease amongst builders around these strategies. After all, your business is still dependent upon somebody owning and operating the assets. And while it is obvious that Airbnb’s business model is the best fit for aggregating supply of previously underutilized assets , there are plenty of others that are contingent on stronger ties between the asset-base and the asset-light operation layer.

Tech operators are increasingly looking at legacy industries and seeing asset ownership as a necessary part of transforming the industry.

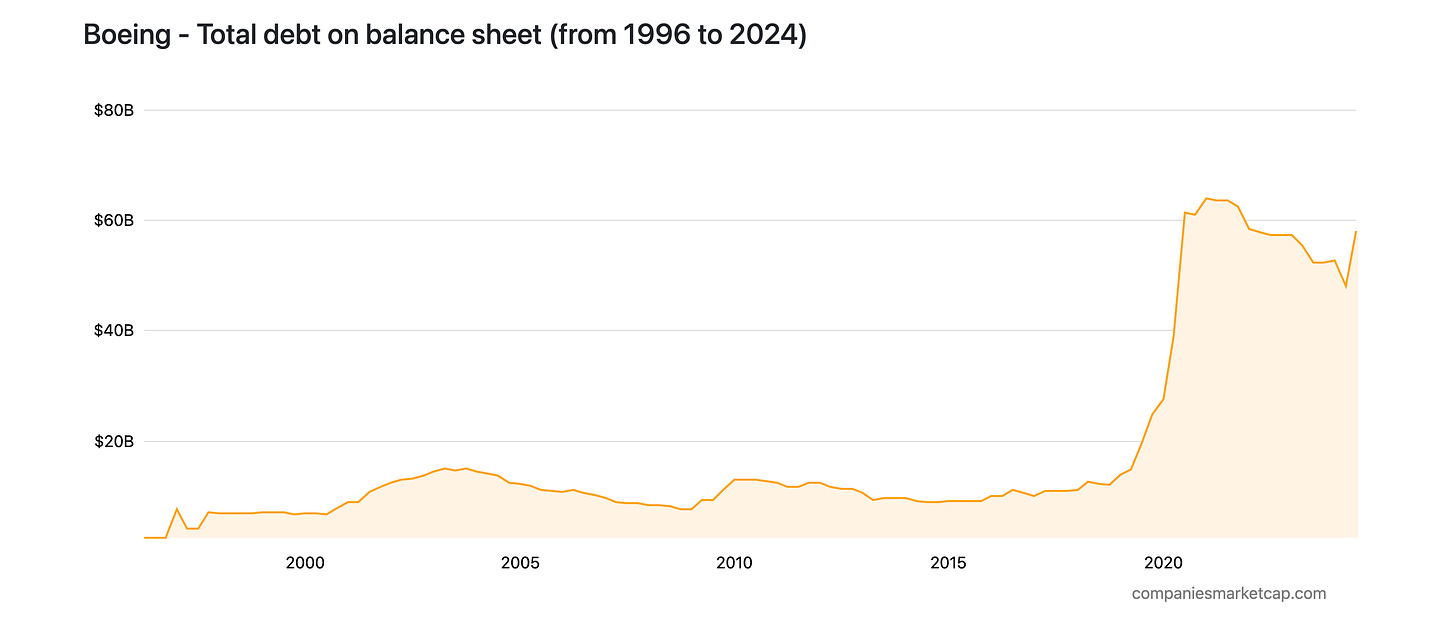

However, asset ownership is incredibly difficult. Look no further than public companies operating in asset-based industries. At the management level, most of these companies look alike: they’re entirely focused on managing the inherent risk in dealing with their portfolio. To do this, they increasingly rely upon debt financing to remove working capital requirements and look “asset-lighter” on the balance sheet.

In practice, these companies tend to act as a management vehicle which also happens to perform some discrete end goal, whether its building railroads, airplanes, or widgets.1

Because financing structures reign supreme, there’s often very little startup scene that has a shot at large outcomes. Startups quickly find that they are not capable of financing the working capital.2 Large financiers simply gravitate towards opportunities that they can forecast more easily.

The majority of new entrants into atoms-based businesses are private equity firms who can apply better management techniques and financial engineering methods to smaller firms. Many of these firms have not applied novel strategies around their operations, but instead have applied paradigmatic management techniques that enable larger firms to gobble up their own rollup.

Even with breakthrough strategy or new products, any startup ecosystem must account for these factors. Managing assets is often a huge and risky hassle.

The conflicting forces become evident:

Asset-light strategies are perhaps the best way to focus upon value creation in legacy industries.

Asset-light opportunities may be reaching end of life due to the proximity required between managing assets and operating assets inherent in most other industries.

The minute you switch into asset-ownership, forces compel you to spend far more energy on managing assets vs. innovation.

It will take plenty of independent developments to reverse these conflicts. But they may already be reversing.

Let’s focus on the two biggest reasons:

The growth of private credit

The evolution of the propco/opco.

Private Credit is Growing

What was the biggest reason fintech as a category took off in the mid to late-2010s?

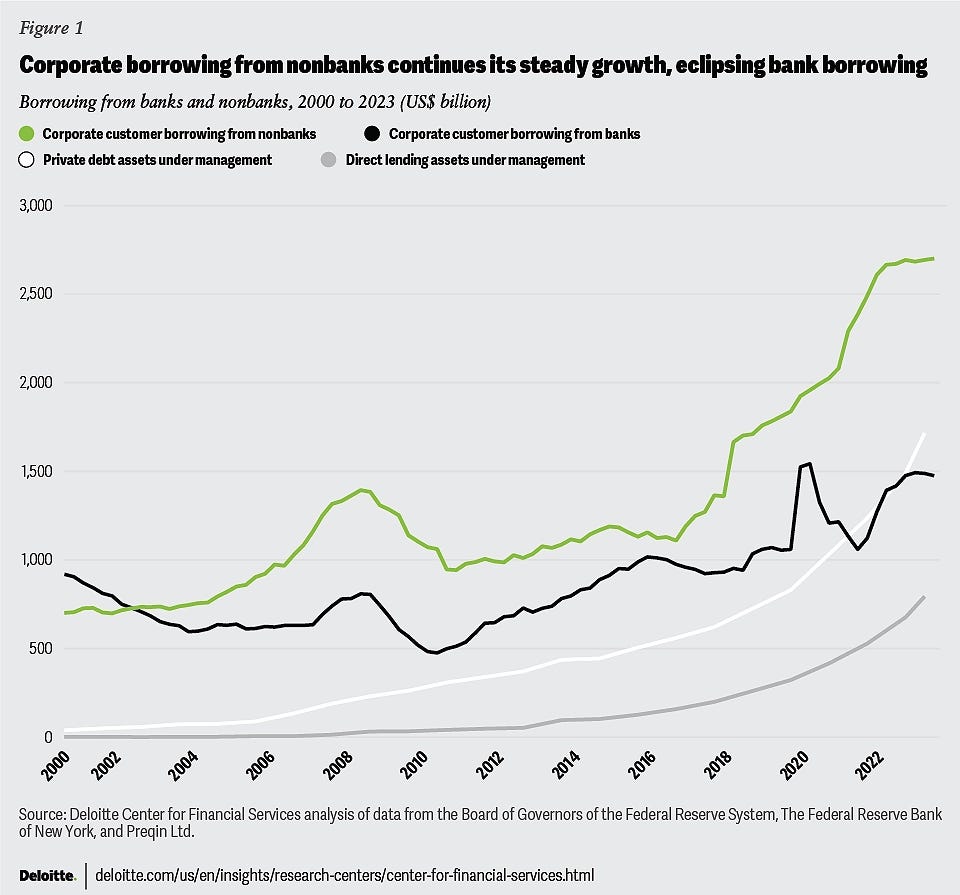

There’s various things you could point to, but I think the one that matters the most is the rise of asset-based private credit funds. A new pool of debt facilities came into the market looking for yield and were often willing to partner early with fintechs to create new financial asset classes.

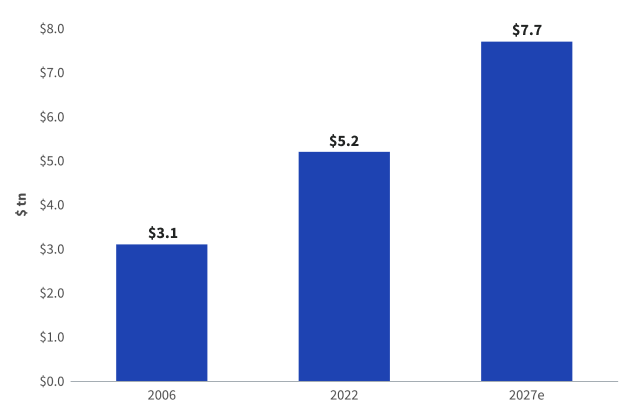

The growth in private credit itself is pretty astonishing.

It took nearly 15 years for private credit to add $2T to its reserves. It will only take roughly 5 more to add another $2.5T.3 At the same time, that private credit is skyrocketing, bank lending has stagnated.

There are many reasons for this but here are a few:

Novel credit strategies are not a good fit for bank lenders. These novel credit strategies are paying off. This is the fintech story in a nutshell.4

Private equity has decisively shifted to private credit as their debt source.

The world has simply become more financially engineered with the banks being relatively tapped out due to a mix of regulations and internal speed.

So what to make of all this?

The demand for private credit has never been higher and the appetite amongst investors for private credit exposure has also never been higher.

The growth in private credit assets is quickly leading to growth in the number of opportunities private credit will look at.

At the same time that builders are looking for asset-based innovation, there is now an investor class looking for yield wherever they can find it.

How will technologists and private credit partner together to capitalize upon this?

An Interlude on Opcos/Propcos

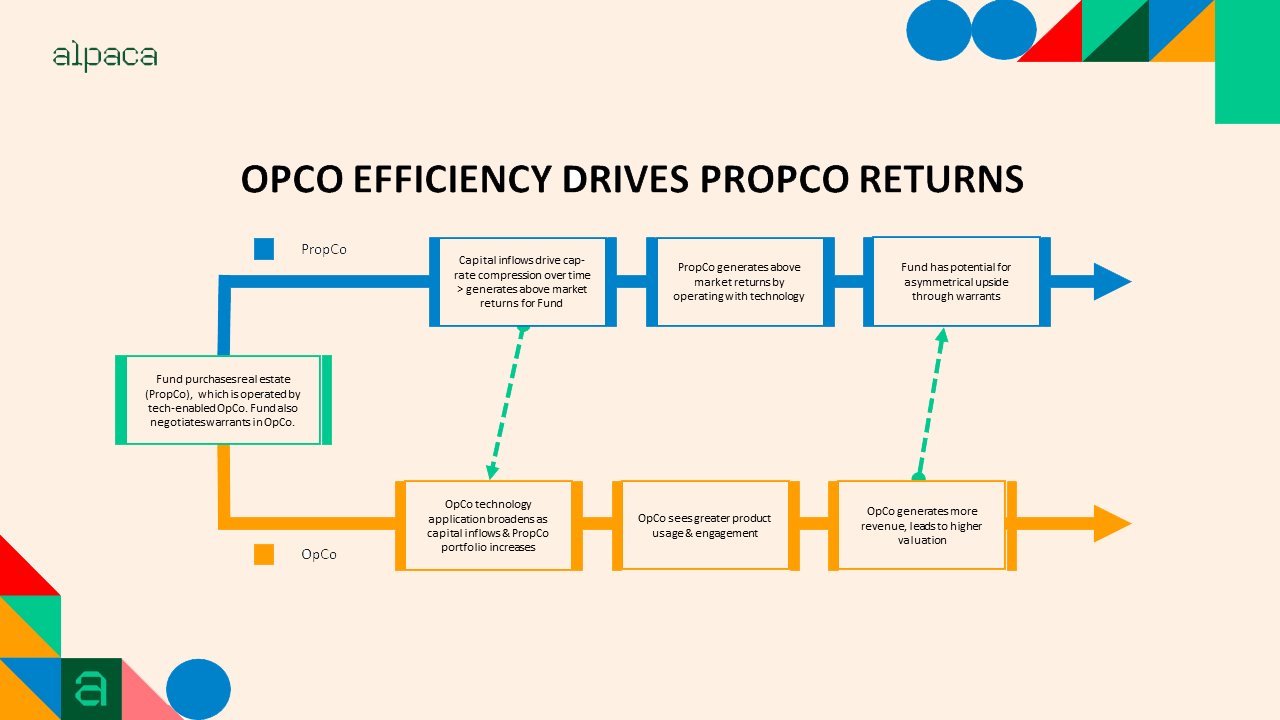

One potential method is through the Opco-Propco model. I won’t belabor the point but, opcos-propcos are a relatively well-known method for tranching investors into different risk profiles. In short, some investors want exposure to asset-light parts of the business: the operation/management company and others want exposure to asset-based aspects: the property company.

There’s various ways to structure these companies. Red Lobster is a bit infamous for their Opco/Propco structure. Sell (red) lobsters through your OpsCo, pay rent to your Propco. But even within REIT-type efforts with some nuance around the exact opco-propco structure, there is more and more reliance upon technology as the operational and management advantage.5

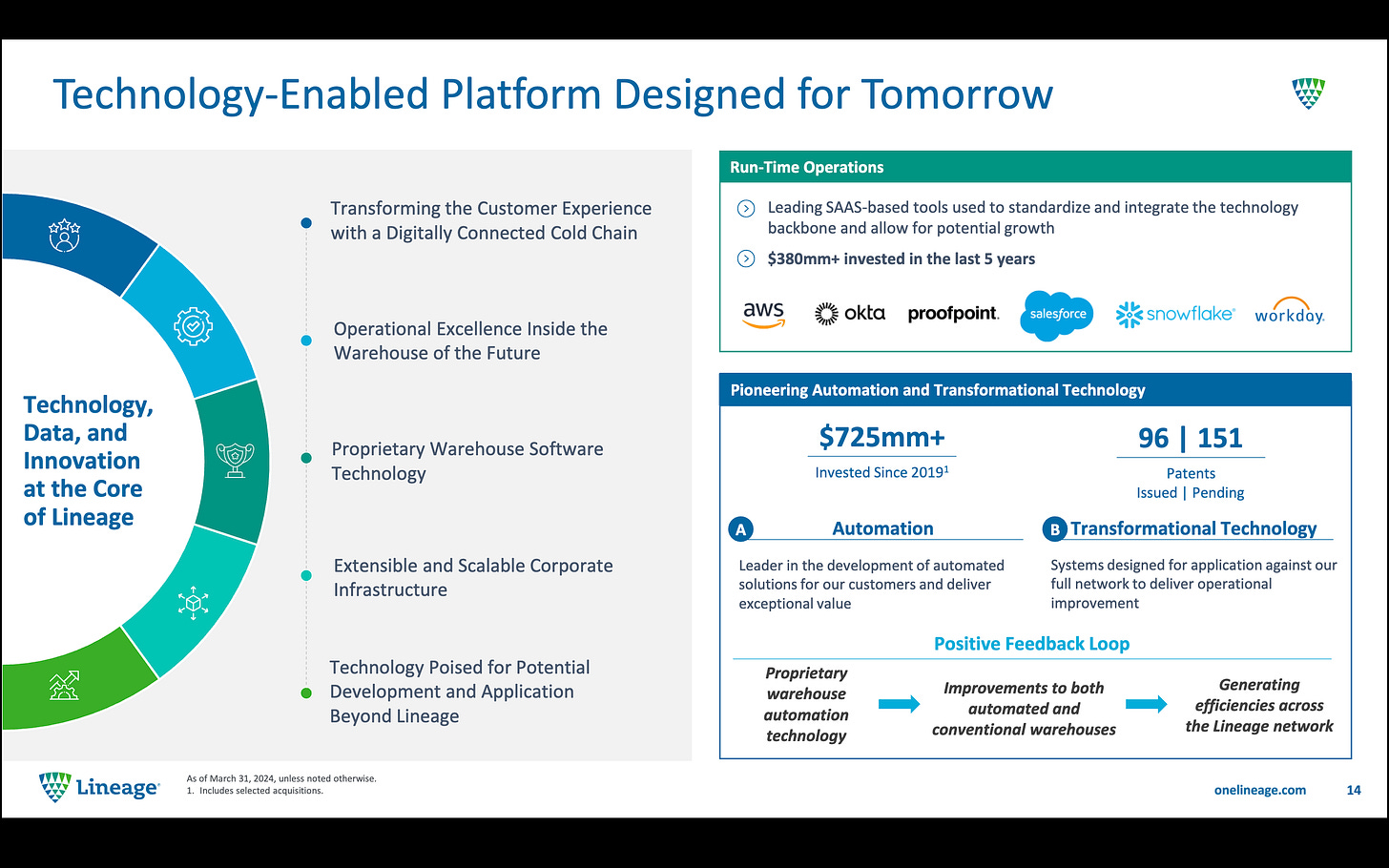

My personal favorite is Lineage Logistics. Their key insight was simple: there was an inadequate cold storage supply chain. You had to both catalyze the real estate footprint for cold storage and operate the assets. The rest is a story of incredible management and structuring revolving around a opco-propco structure to build one of the largest cold storage REITs out there. Alongside their real estate playbook, they’ve spent more and more time building out an integrated automation and services layer.

There are theoretically no limit to the number of companies that can be structured as a REIT, opco-propco arrangement, or draw lessons from the overall structure. So long as there are assets with a known yield profile, the private credit markets are increasingly jumping at these opportunities.

Opcos/Propcos for tech-driven strategies have not fully taken off yet. But my hunch is that you will see more interest in this segment. Why? Because tech-driven strategies are increasingly the basis for novel underwriting and for novel returns on assets. This too is a massive component of the fintech story; fintechs underwrote deals that were impossible to do without software and ML enabled underwriting.

As this plays out, we would expect private credit to increasingly recognize that technology can create leverage both in a) the underwriting of assets and in b) the operation of assets outside of fintech related industries. Utilizing technology to perform unique underwriting and operations will increasingly be the lever that opco/propco structures build their business around.

New Financing and Underwriting Arrangements:

The lesson of fintech and vertical SaaS is that to the extent there’s a new line of payments volume, financing, or structuring that can be captured by a disruptor alongside the asset class they are financing, the juicier the opportunity.

Several models have been tried over the past few years that have utilized innovative financing and underwriting methods to build ownership positions in new financial instruments.

Two of the better known ones are:

Rent-to-own models:

ESOP Structuring:

Key to these models is an insight: increasing liquidity in assets via new instruments is often the best way to build a new opco-propco model altogether.

In these cases, companies focus on an opco that is concerned with new data and underwriting strategies with an ancillary focus on operating the assets that result, while the propco provides the capital for acquiring the underlying assets.

And in fact even in traditional industries, we can see opco/propco models working to quickly accumulate novel assets.

Opportunities abound.

Minerals + Oil and Gas:

Kobold Metals is in essence a land underwriting company. They use incredible ML models to predict where rare earth metals lie and then acquire land prior to competition. It’s worked in a big way. They’re currently spending their time on about 60 different exploration sites after discovering one of the largest copper deposits in Zambia.

My hunch is that there are plenty of other opportunities for novel propco-opco models involving land and mineral rights.6

Real Estate:

Within real estate, propco-opcos hold plenty of potential avenues for new opco-propco models.

Last week, we talked about Blue Jeans Golf. Opco/Propco structures give the ability to tranche investors into groups who want land value appreciation and rent income and investors who want direct exposure to the Golf Ranch brand.

Perhaps merely the business of structuring REITs to help enable innovative real-world companies becomes valuable.

"Surprisingly, while OpCo money is most at risk and should theoretically be harder to access, the real funding gap in the market lies on the PropCo side." - Thibault Weston Smith (Co-Founder, Crayon Partners)

- taken from Cherry Lawn’s Transitional Capital

Structurally, most acquisition based businesses are not a fit for opco/propco models. Or at least, they aren’t pure play opco/propcos. However, many business owners are structurally incentivized to sell any real estate holdings as part of their acquisition but while acquirers are often willing to take on the real estate, it’s often not mission critical. There are many reasons why owners wish to exit the real estate as part of the business sale:

The real estate has intrinsic value that may actually give rise to a higher exit price than the underlying business.

There is ultimately no point in managing the real estate if the underlying business is sold. Most owners have no compounding advantage in owning the real estate.

The value creation of a rollup has little to do with real estate operations. It is not a focus nor do most rollup strategies reach a scale where deploying sophisticated real estate strategies creates much value creation above and beyond operational synergies.

So why not utilize a novel opco-propco strategy to potentially solve this? I’m in the early days of exploration here, but will write more in the future.7

Energy

The energy transition has been bottlenecked by deployment. Here too, private credit is looking to bridge the gap. As Packy notes, when we talk about batteries, we are talking about a deployment problem that somewhat stems from a gap in financing.

For one thing, batteries are expensive. Customers understandably don’t want to pony up $15,000 for something that pays itself back in 12 years even after the 30% IRA tax credit.

Private equity-backed battery farms like Broad Reach (Apollo), Jupiter (BlackRock), and aypa (Blackstone) on the other hand, are happy underwriting that investment, signing offtake agreements to sell their power, and levering the hell out of it at 70-80% loan-to-value to generate high levered returns.

In that space, Base Power has entered with a bit of a novel model but with the same basic idea: private credit will be fundamental to the company’s success.

For now, Base is financing batteries off of its own balance sheet. In the months ahead, it needs to grow the portfolio and prove out the economics of its batteries so that it can secure asset-backed loans to fuel its growth. Building a portfolio that appeals to lenders means that Base can unlock a lower cost of capital, which means more batteries and more profits, and ultimately even lower costs of capital. The moat widens.

Across the economy, the question is morphing from “can software transform this industry?” and into a new question: “what is the correct capital structure that enables my team to maximize the leverage ML/AI/hardtech in this industry will give me?'“

Much of the frustration with legacy defense primes, Boeing, and more is really an observation that product people do not run the company.

The exception of course is in defense tech which had Anduril simply solve the financing structures by raising massive amounts of equity capital.

And some will put this at another 4T.

Equity investors were not the biggest beneficiaries from fintech, private credit was. Market caps are unimpressive, but the credit returns are huge.

Many large hotel REITs were created as the propco spinoff of a previously unified opco-propco company.

The rise of drones plays hand in hand with novel possible strategies.

Part of the reason this is so interesting is that the assets themselves are illegible and it’s a massive prize pool.

Your analysis of opco/propco models in the context of tech-driven strategies is excellent, and Lineage really is the perfect example. What's interesting about their approach is that they didn't just separate real estate from operations - they used the structure to create a flywheel where the PropCo's scale enabled better OpCo margins through automation and softwar integration. The cold storage market had terrible fragmentation, and by combining better underwriting (knowing which properties to acquire) with operational excellence (automating them), they've essentially created a moat that pure-play REITs or pure tech companies couldn't replicate. The private credit angle you mention is spot on too - these structures only work when you can secure the right debt partners.