Leverage through Joint Ventures

analyzing Kobold Metals and mining exploration partnership structures

Good morning!

This is some of the most fun I’ve had writing a piece.

We need far more analysis around the unique ways companies in industries are going to use their inherent capital and technology advantages to transform industries.

As we leave the pure-play SaaS era, some of the most fantastic opportunities will demand new balance-sheet constructions, asset-based financing, and creative partnership structures.

Dealmaking is destiny.

Kobold Metals is one of the greatest dealmaking companies around.

The defining feature of Kobold is its ability to exercise leverage across partnership and capital structures—unlocking the value of its technology to discover rich mineral deposits around the globe.

You can tell one story about Kobold as an AI company, but you can tell an even better one about Kobold as a company that exercises this leverage to solve the political and partnership ramifications of drilling for billions of dollars worth of rare earth minerals.

A refresh

Kobold Metals is a minerals exploration company that explores in areas where rare earth metals can be potentially located. That means lithium, that means cobalt, that means copper. That means an assortment of potential mineral interests that are necessary for the future of electrification and that come with massive geopolitical ramifications.

A primary issue is simply identifying sites that can support large-scale mining operations. While these minerals aren’t rare, they are difficult to find for a number of reasons. Most of the best active mines are in the Chinese’s orbit of influence. That geopolitical reality means much of the rare metal space is effectively closed off to U.S. companies.

And simply put, there’s no low-hanging fruit anymore. Kobold Metals came onto the scene with one critical idea: what if we could leverage AI and machine learning to identify the highest propensity drill sites for exploration, discover large deposits of critical minerals, and subsequently capture a large part of the upside in bringing these sites to production?

To do that, they have a two-pronged approach around their technology: TerraShed now hosts somewhere between 3% to 5% of all geological records across the globe.

The idea here is to literally extract decades old written copies of geologic reports, satellite imagery, and maps from places like Zambia into a unified database. It is no small feat to simply obtain this data and normalize it into a unified map.

Once they have this data, they then leverage Machine Prospector, their ML platform, to identify the highest propensity sites for potential mining activity. And then the fun ensues.

The State of Mining

The mining industry can essentially be broken down into three core categories, with, of course, some overlap.

At Scale Mining Companies: These have assets in production and usually also have projects at the exploration phase. These are mature businesses and well managed.

Junior Miners/Exploration Companies: These companies are typically speculative. They possess the rights to mineral interests in defined areas, but quite often have minimal funding to properly explore their claims. This is a huge problem. Theoretically, there are a large swath of minerals that are underground, but we wouldn’t have any idea due to the inadequacies of companies sitting on these claims with nearly nothing to show for it.

Governments: The greatest single blocker or aid in mining. Governments may lack technical savvy, but if you find a deposit worth anything, you better be ready to cut deals in order to get these minerals out of the ground.

And so, if the biggest blockers to new mining projects are, quite frankly, land speculators or governments who have been burnt before, the entire success of the business does not depend upon necessarily your technology.

It depends on how you can structure partnerships and incentives that enable you to quickly establish whether there is potential in a region, but not overcommit if there isn’t. The entire ballgame for success relies upon structuring these deals.

And so how do you get deals to the table? That is all about technology and financial leverage.

Technology + Capital Leverage

Let’s say you have two things in mining exploration that nobody else has: technology and a balance sheet worth billions.

What do you do? The pain points are twofold.

First, much of the land worth exploring already has a mineral claim on it - you need to get access. It’s time to cut deals.

Second, you can’t afford when obtaining this access to be in for a penny, in for a pound. You’re dealing with mining companies hungry for capital; that see your balance sheet and see opportunity.1 You need early opt-outs. You need the right to walk away, and you need majority upside with minimal downside.

Check out this interview with the CEO of Libra Energy in Canada to get an instant perspective on how successful Kobold has been in achieving these objectives.

Skip to 40:03 if it doesn’t autoplay from there.

The dollars that [Kobold] is going to have to put into this [JV], exceeds what our company valuation is.

Ladies and gentlemen, that’s leverage.

So to explore what these joint ventures entail, let’s do a brief tour through what Kobold was able to extract in this Joint Venture.

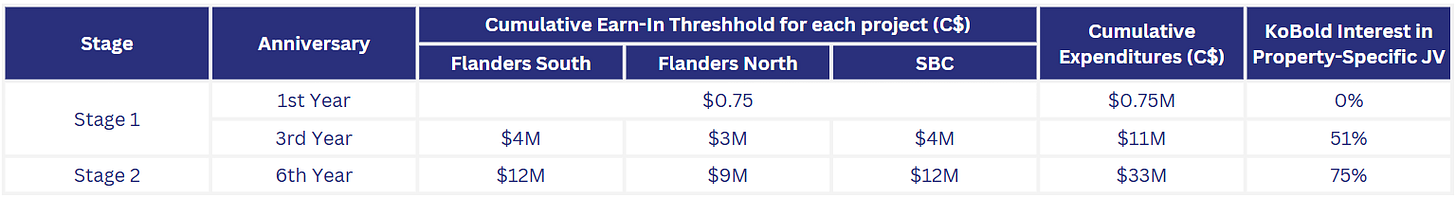

The deal between Libra Energy and Kobold is structured around an earn-in interest. Essentially, Kobold has to commit to spending enough money on mining exploration activities to obtain a Joint Venture on the underlying mineral claim.

In this case, Kobold committed to spending $33m in exploration activities on 3 properties in Libra’s portfolio.2

Some things to note about the deal:

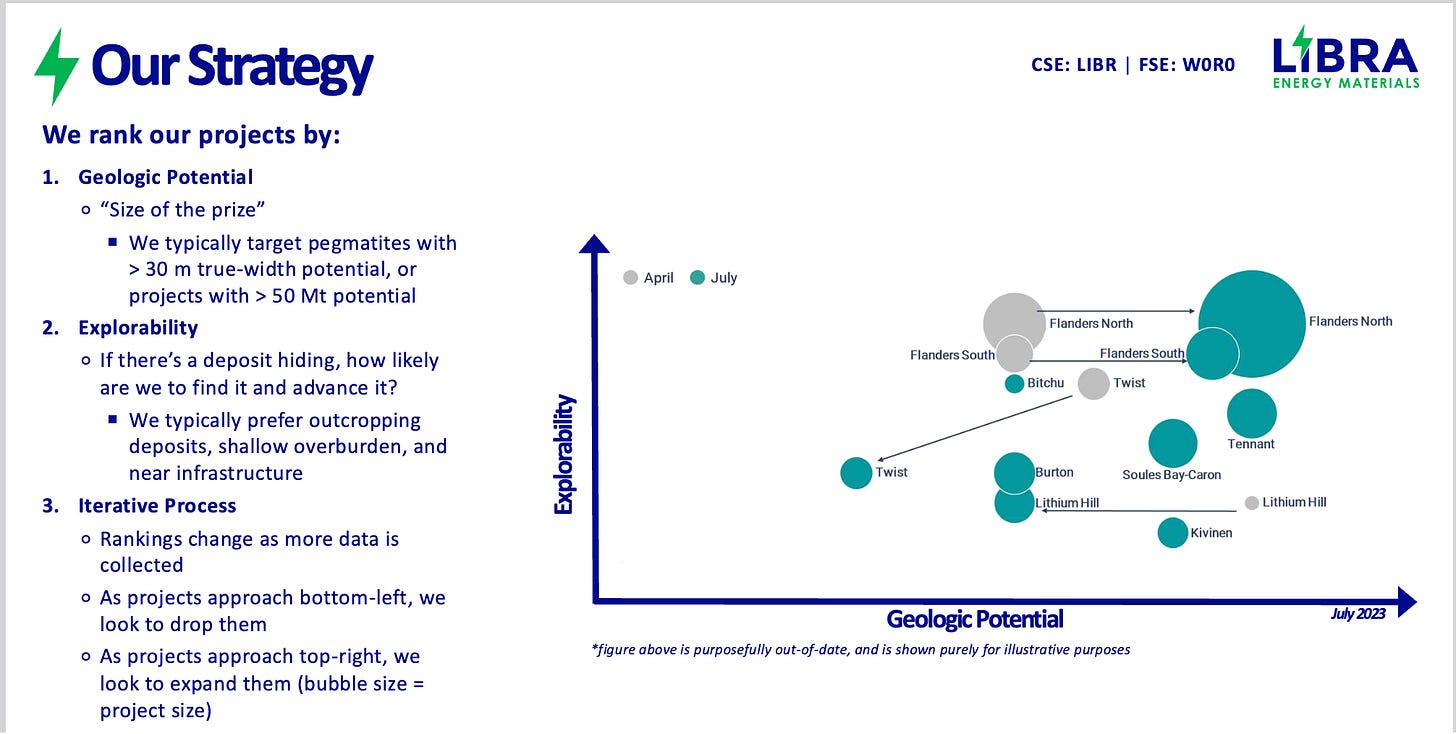

1. They got the best mining claim sites. Kobold was only interested in three mining sites for exploration: Flanders North, Flanders South, and Soules Bay-Carron.

It turns out those are 3 of the 4 best potential sites in Libra’s portfolio.

They maximize their partnership interest. If Kobold performs $33m in exploration activities over 6 years, they will own 75% of the joint venture. And you better believe (as we will see later), that they are only committing that $33m if there’s going to be a huge outcome.

So in short, Kobold can bring in proprietary technology into land with active mineral claims, determine relatively quickly if there’s potential, get vast upside if there is, and nearly no downside if there isn’t.3

And so it’s no surprise that Kobold has structured a large swath of JVs.

Kobold’s Joint Ventures

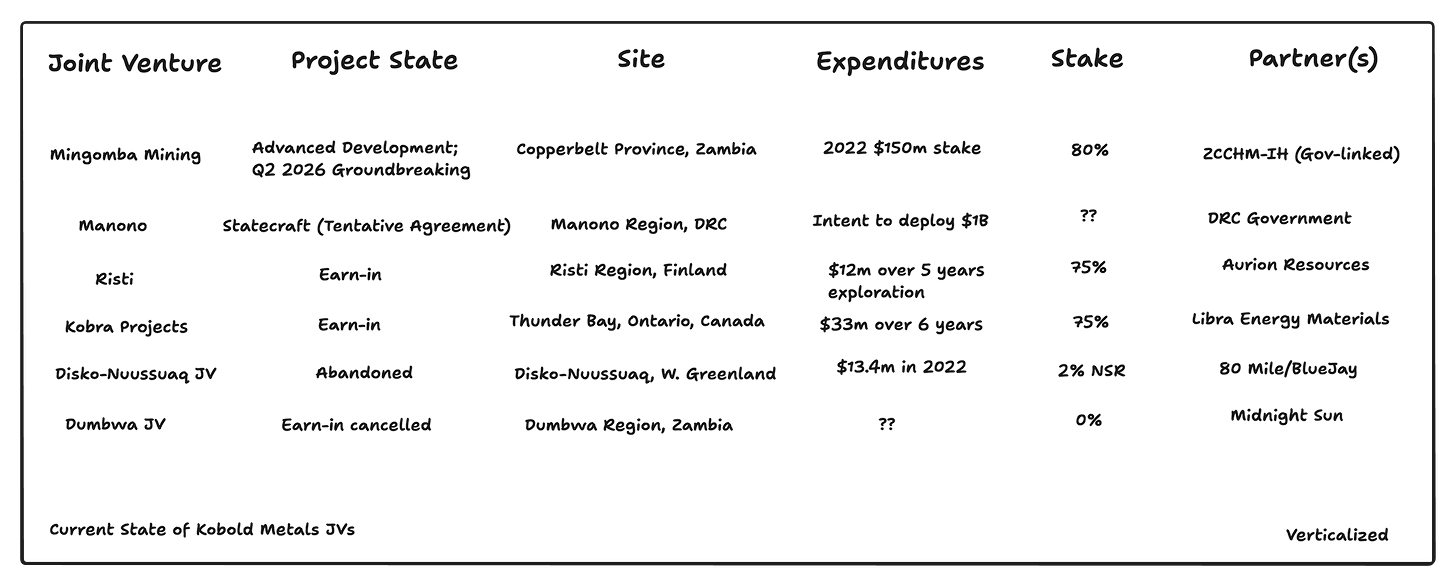

I wanted to give you a brief glimpse into the breadth of these JVs. If there’s a region in the world where there’s a viable path to a mine, my guess is Kobold already has or is structuring a JV with partners to enable exploration.

And there’s one other important thing we can glean here. You’ll note that there’s two projects that have been subsequently abandoned by Kobold during either an earn-in period or during the early process of a JV.

In both cases, what’s remarkable is how quickly Kobold entered and then left.

The Greenland project was one of their earliest announced JVs. The partnership was formalized in 2022 and officially ended this year. But Kobold? Kobold was in and out. According to the press release, Kobold only did exploration activities during 2022.

We can surmise that they didn’t like what they saw and quickly bounced. Now, their expenditures here were $13.4 million. My guess is that in every subsequent JV, (because again, this was their earliest) the initial mining exploration projects to determine mining viability are going to decrease. There’s simply too many gains to be had in one company from technology improvement and human talent learning curves.

A similar situation occurred with Midnight Sun mining in the Dumbwa JV. Kobold was in and out within a year.

If Kobold doesn’t reach a positive determination quickly or if there’s complications with their JV counterparty, their team has shown a willingness to get out fast.

The crowning achievement thus far of Kobold is on the Mingomba mining joint venture. Kobold initially bought a $150 million stake in the region in 2022, subsequently discovered positive results, and then ended up discovering that this could be one of the largest mining projects for copper in all of Africa.

This too is a JV construct. Except this time it’s with a pseudo-government-aligned organization. It used to be a fully public government enterprise until some international banks forced the mining company to go private. This is essentially the biggest provable milestone thus far that Kobold has incredible advantages, not only on the JV side, (they were able to extract 80% of this stake in the mine), but also in their technological ability to go further within two to three years to determine the viability of a mining operation. The net revenue from this project is going to reach billions of dollars. And that opens up an entirely new dilemma. Because after all, once you’ve uncovered something worth billions, statecraft comes into play.

Statecraft

Building a mine after exploration is a multi-year process with constant negotiation and renegotiation and that increasingly involves geopolitical negotiation. It requires deal-making acumen across financial markets and political actors. Kobold CEO Kurt House has had to spend myriad amounts of time across the Biden administration, Trump administration, and across the Zambian government, ensuring that there are no key blockers to building the mine and subsequently being able to export mineral resources into other countries.

For instance, the Biden administration at the tail end of 2024 negotiated the construction of the Lobito Corridor, which is designed to connect the CopperBelt region to a port.4 It’s does you no good if you mine a resource but not get it shipped. And as always, if there’s a large enough underlying mineral value to be extracted, everyone’s elbows come out. Building the mine on expedited time horizons are not only matters of capital efficacy but of geopolitical viability. If you don’t extract the resources fast enough for the state to be made whole and to fund often their entire government, you risk losing control of the project altogether.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Perhaps this is most clear in the DRC, where Kobold has also purchased 100% mineral claims throughout the Monono region.

Importantly, here, this is being litigated! Now, this is not legal analysis, but here’s my interpretation of what happened. A prior mining company named AVZ Minerals had the right to mine lithium in this region. The lithium deposits were documented and yet there’s still no lithium being extracted. As a result, the DRC terminated AVZ’s licenses, saw Kobold Metals success in Zambia, and went all in on enabling Kobold to find and extract lithium in the region.

Suffice to say, this did not go over well. And after international hearings, legal determinations, the AVZ should not have been kicked out, tentative agreements between Kobold and AVZ for Kobold to acquire the interests, and subsequent scuttlebutt since then, Kobold has the permits and is ready to commence activities.

Again, leverage is everything. Elbows out and cut deals to unlock rare earth minerals. The critical bit of success for Kobold is not solely its technology, it’s their success at maneuvering these issues of statecraft and coming up on top.

Asymmetric Returns from Leverage

All of this amounts to a company capable of creating asymmetric bets at a scale that nobody else can.

So once more let’s document the core drivers here of this success.

Their balance sheet allows them to walk away.

Having a larger balance sheet enables them to take asymmetric bets and walk away the instant they don’t see upside. That’s a fundamentally different approach from what many of these other companies can tolerate.

Their technology and team enable them to reach these determinations far faster than a traditional explorer ever could.

Because of these unfair advantages, if minerals are discovered, they obtain nearly all the economics. These economics will be the critical driver of the next 30 years at Kobold. With measurable revenue comes new tradeoffs. Does it make sense for incremental dollars to go towards new exploration or towards mining efficiency?

Future

As Kobold begins to develop mineral deposits into fully operational mines, it will be fascinating to watch how their JV structures morph.

Right now, Kobold is willing to tolerate exploration expenses of areas that display potential for large scale mining projects.

But as they identify these assets and own mines that produce billions in copper and lithium a year, will they narrow down their strategic exploration projects?

Let’s remember that minerals are commodity markets. A glut of copper supply or cobalt supply will reduce the price of the minerals you’re extracting. And so an interesting dilemma may settle in. Remember, timelines are everything in mining. Your joint venture partners may not be interested in tolerating a 15 year build out timeline in order to protect your other interests from a glut of supply that renders it uneconomical. And so will we see joint ventures morph into full acquisition of the underlying mineral claims? The jury’s out. But as Kobold brings mines into production, the subsequent phase of their deal making will become fascinating to watch.

Thanks for reading. More to come this Friday.

If your technology and talent are good, you shouldn’t need decades. You should be able to render initial decisions on mining viability within the first year or so.

They’re also essentially funding the G&A of Libra (35k a month) over the earn-in lifecycle.

Financially, I would be extremely curious to know how mining expenditures are measured. There’s obviously capex components, but I’m also fairly sure that this is including a fee for their platforms, data teams, people on the ground, and more. Does $33m in mining expenditures reflect $33m in actual expenditures by Kobold on a specific site project? I’m not convinced!

And also connects their projects in the DRC.